Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the University of Cambridge, The Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research (FMI), Switzerland, EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI), and collaborators, have created an in-depth picture of how the placenta develops and communicates with the uterus. This study is part of the Human Cell Atlas initiative1 that is mapping every cell type in the human body.

The paper, published on 29 March 2023 in Nature, details new information that was not possible to gain through previous methods and compares the findings to placental organoids, ‘mini-placentas’, that can be grown in the laboratory. This research informs and enables the development of these experimental models of the human placenta.

The placenta is a temporary organ built by the foetus that facilitates vital functions such as foetal nutrition, oxygen and gas exchange, and protects against infections.

The formation and embedding of the placenta into the uterus, known as placentation, is crucial for a successful pregnancy. Understanding normal and disordered placentation at a molecular level can help answer questions about poorly understood disorders that include miscarriages, stillbirth, and pre-eclampsia.

In the UK, mild pre-eclampsia affects up to six per cent of pregnancies. Severe cases are rarer, developing in about one to two per cent of pregnancies2. Generally, many of the processes in pregnancy are not fully understood, despite pregnancy disorders causing illness and death worldwide. This is partly due to the process of placentation being difficult to study in humans, and while animal studies are useful, they have limitations due to physiological differences.

During its development, the placenta forms tree-like structures that attach to the uterus, and the outer layer of cells, called trophoblast, migrate through the uterine wall, transforming the maternal blood vessels to establish a supply line for oxygen and nutrients.

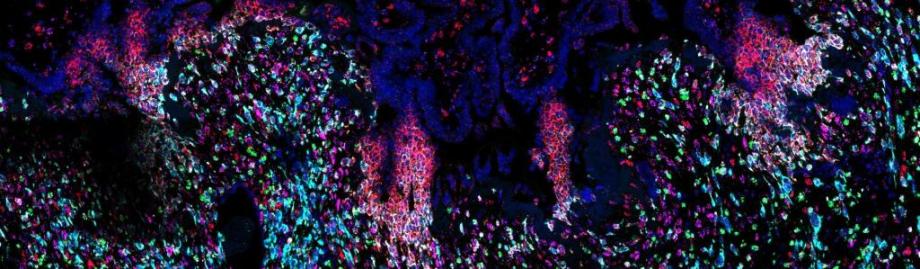

In new research, scientists built on previous studies investigating the early stages of pregnancy and applied cutting-edge single-cell genomics and spatial transcriptomics3 technologies to a rare historical set of samples4, capturing the process of placental development in unprecedented detail. These genomic techniques allowed researchers to see all of the cell types involved and how trophoblast cells communicate with the maternal uterine environment around them.

The team, from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and collaborators, uncovered the full trajectory of trophoblast development, suggesting what could go wrong in disease and describing the involvement of multiple populations of cells, such as maternal immune and vascular cells.

The team also compared these results to placental trophoblast organoids, sometimes called ‘mini-placentas’, that are grown in the lab. They found that most of the cells identified in the tissue samples can be seen in these organoid models. Some later populations of trophoblast are not seen and are likely to form in the uterus only after receiving signals from maternal cells.

The team focussed on the role of one understudied population of maternal immune cells known as macrophages. They also discovered that other maternal uterine cells release communication signals that regulate placental growth.

The insights from this research can start to piece together the unknowns about this stage of pregnancy. The new understanding will help in the development of effective lab models to study placental development and facilitate new ways to diagnose, prevent, and treat pregnancy disorders.

Anna Arutyunyan, co-first author from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and the University of Cambridge, said: “Despite the placenta being a vital organ that plays an important role in everyone’s life, its development is poorly understood. Although we have previously seen how the structural cells of the placenta, trophoblast cells, attach and start to travel through the maternal uterus, the existing resources and models have limited further understanding. For the first time, we have been able to draw the full picture of how the placenta develops and describe in detail the cells involved in each of the crucial steps. This new level of insight can help us improve laboratory models to continue investigating pregnancy disorders, which cause illness and death worldwide.”

Dr Margherita Yayoi Turco, co-senior author from the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research (FMI) in Basel, Switzerland, said: “Using a systems biology approach, this work captures and describes the specialised placental extravillous trophoblast cells as they invade the maternal uterus during early pregnancy in humans. It provides an essential resource that will help improve our understanding of the maternal-fetal interactions that are critical for a successful pregnancy. Our knowledge about early placentation in humans is limited. Only with the combination of expertise from computational biology, human reproduction, organoids and stem cell model systems, and with the use of historical and rare pregnant hysterectomy samples, has it been possible to shed light on the processes occurring during this critical time that determines pregnancy outcome.”

Professor Ashley Moffett, co-senior author from the University of Cambridge, said: “Studying pregnancy in humans is difficult, but is necessary if we are to help prevent and treat disorders that arise throughout gestation. This research is unique as it was possible to use rare historical samples that encompassed all the stages of placentation occurring deep inside the uterus. We are glad to have created this open-access cell atlas to ensure that the scientific community can use our research to inform future studies.”

Dr Roser Vento-Tormo, co-senior author from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “Successful placental implantation is an important step in pregnancy, and many pregnancy disorders, such as pre-eclampsia, can be linked to issues in its development. Insights from our research show that our previous understanding of placental implantation was incomplete and that the maternal uterine cells release communication signals to encourage placental growth. Understanding the communication signals through spatial data gives us a fuller picture of how the two organs, the placenta and the uterus, work together highlighting where issues could arise in disease.”

Image credit: Kenny Roberts, Cellular Genetics, Wellcome Sanger Institute